“Forget your lust for the rich man’s gold

All that you need is in your soul

And you can do this, oh baby, if you try

All that I want for you, my son, is to be satisfied”

– Simple Man. Lynyrd Skynard

There is a street in Brighton, Sydney Street (which for some reason always brings to mind a chuckling Sid James) where I like to sit – if it’s warm enough – outside, sipping a latte and thinking about….well, thinking about what comes next.

And as I perched outside my favourite café in my favourite Promised Land street, I was in the middle of thinking about what comes next, when the first of many fly-pasts for money from shuffling (or scurrying, depending on the level of intoxication or ingestion) began.

I calculated that, while I had been sat for barely five minutes, I was approached at least five times. It may have been six. Was this a record, I wondered?

Could be my pleasant, unassuming demeanor, I thought. Or the fact that I looked prosperous enough, deep in thought in the late autumn sunshine, to be worth a go.

As a rule, I rarely give money to those who ask me in the street. It’s discouraged in Brighton, where we have the second biggest homeless population in the UK after London. They just spend it on drink and drugs, is the usual refrain.

Could be, but every one of those people who asked me for money on a day when the last of the summer warmth began to make way for chillier autumn afternoons had at least one thing in common. They had no money.

It’s down to personal choice, many will say. Circumstance. Miserable, hellish environmental backgrounds. Whatever. It boils down to zero dinero.

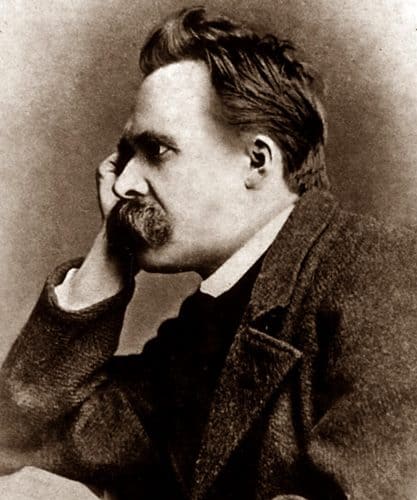

Some of the greatest minds in civilization have also suffered debilitating anxiety over a lack of funds. Think of Mozart, of Chopin and Malcolm Lowry, of Nietzsche and James Joyce and Shakespeare.

They all scraped by, more or less – although for Wolfgang Amadeus the debtors’ prison and abject penury were an uncomfortably prevalent daily worry. The constant knocking on the door. The looking nervously over your shoulder.

Fast forward a few hundred years and it’s looking like many of us in first world UK are also deeply concerned about the wonga – as my old editor of CM passim Richard Smith (RIP) used to say – reserves.

According to a story buried deep in the Financial Times (September 2019), one in three of those in work have wonga reserves of just £500. The news piece – based on research put together by an employee benefits’ organisation called (unimaginatively) Salary Finance.

The company’s research (I use that term guardedly) revealed that workers with financial worries are more than four times more likely to be suffering from anxiety and panic attacks, and 4.6 times more likely to be suffering from depression.

Inevitably, financial wellbeing has a significant knock on effect on absenteeism, productivity and staff retention. But one in three workers suffering?

It’s a big number.

While I am sceptical as to whether that £500 war chest in reserve for a third of working people figure will stand forensic scrutiny, what is not in dispute is the fact that we – currently at least – have an employment rate of 76.1%. That’s the joint-highest on record since comparable records began, way back in 1971.

Economists do not yet know how the current Brexit mess will impact on employment figures (lay-offs would seem inevitable) – but as at June 2019 we had 32.81 million people aged 16 years and over in employment.

The recent collapse of Thomas Cook, with all hands-on deck, will of course dent these employment stats – around 9,000 workers have lost their jobs in the wake of the consignment of this once proud name to the High Street reject bin of history.

And, sitting under the lengthening shadows of the awning of Dave’s Comics in Sid James Street, I ponder that, in sociological terms at least, street beggars, homeless people and those unfortunate enough to be at the lowest strata of society are deemed to be highly socially invisible. Which seems to me an anthropological paradox.

I mean, they couldn’t be any more visible….could they?

The ever-deepening rift between the haves and the have nots in our society is not just desperately troubling, it is surely no longer tenable.

As the full extent of the salary and obscene bonus raid on the Thomas Cook coffers by the now defunct firm’s senior executives is rolled out from the board room and into the public domain, together with the shoddy and brutal way loyal employees were left high and dry, it is staggering that lessons from the past have not been learned.

Following the financial collapse in 2008, those investment bankers – most of them, as it turned out – who held onto their jobs, continued to enjoy inflated incomes and perks, while Joe Working Public was condemned to a decade of austerity. Hundreds of thousands lost their jobs.

Now, a decade and more on, clearly, no lessons have been learned. And we are witnessing yet another prime example of wholesale collapse due for the most part to successive corporate bungling and mismanagement.

That recovery to a full employment economy has come at great cost, month by painful month – yet it now appears to be gravely imperilled. A winter of discontent looms.