DO bank managers still exist? I mean, in the old-fashioned sense of the term. You know, like back in the days when you needed to borrow some cash and there was not an instantly approve (or reject) online facility. In ye distant far off times, the protocol was to make contact with your bank, and, invariably, request an interview with the Chief Beak.

Those were of course also in the days when our high streets were festooned with bank branches, as opposed to wall to wall charity shops and – if you are really lucky – a branch or two. The more rural the location, the less likely you are going to find a ‘proper’ bank branch in 2019.

Today, like millions of my fellow citizens, I bank online, and for the most part via the fabulous apps on my mobile telephone. First Direct – which I initially joined in 1991 when it debuted as the UK’s first all singing, all dancing telephone bank, now offers a superb online service, and it is rare indeed for me to have to physically call the bank. Likewise, with my other lender, HSBC – which happens to own First Direct.

On the occasions when I need to pop into my local HSBC branch to discuss my company account, I am ushered into the Business Pod, where my account is dealt with politely and efficiently.

Banks have of course taken many knocks over the years. And I don’t just mean the investment arms of the international lending establishments, whose complex intra bank lending were seen by most analysts of the 2008 crash to have been responsible for the near collapse of the UK’s banking system and the overnight annihilation of our economy.

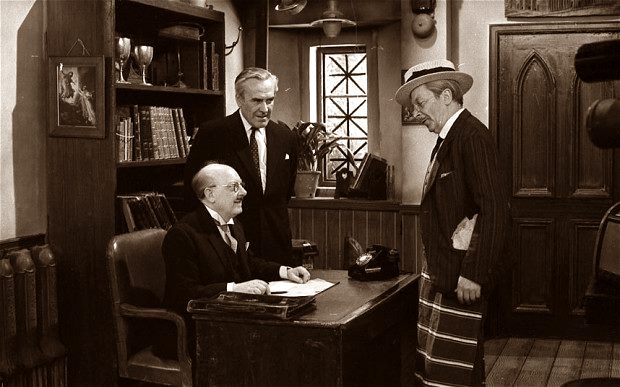

No, the current bad boy image is largely down to the fact that banks are not only closing physical branches in increasing numbers of provincial towns and rural villages – not to mention inner cities – but many fear they are not doing enough to counter the shutting down of ATM machines across the UK.

So, first the bank branches go, and then the cash machines. According to a recent Which? report (March 2019), around 3,000 ATMs were closed in the last six months of 2018. Currently, around 300 machines are being shut every month. It is a worrying trend.

It is partly because people are using cash less, thanks to the rise in popularity of new payment methods such as contactless transactions. My kids – as I am sure other parents of a certain age have discovered – never, ever have any cash.

But it is also because cash machine operators such as Cardtronics and Note Machine, who get a fee from our banks each time we use one, are finding that fewer of their machines are economic to run.

A myriad of reasons then, and it’s fair to say that for those of us who live in major cities, it is not a problem – yet. But for millions of countryside dwellers – many of whom now must rely on driving or using public transport just to access a cash machine – it is a significant issue.

Speaking as one who was perpetually skint through university days, getting hold of cash was mainly an issue as I seldom had any money in my bank account.

Not that this stopped me from going vertiginously overdrawn, seemingly after the first couple of weeks of term time – even though you could get four pints for a quid in my student union bar in the late 1970s.

In fact, the last time I had a physical, face to face meeting with my old NatWest bank manager (Colchester branch, January 1979) he benignly asked if I had my cheque book and bank card with me.

I do, I said.

Thank you, may I have them please, said the affable boss, whose name has escaped me down the mists of time.

Passing them across the forbidding terrain of a huge teak desk, my then manager calmly relieved me of the offending merchandise, while simultaneously retrieving an enormous pair of scissors from a drawer and expertly snipping my bank card and cheque book into small pieces.

Like confetti, I recall thinking at the time. Chastised, I nodded solemnly as he outlined a repayment plan for me to weigh off the bank. According to the Office for National Statistics’ composite price index, £300 in 1979 is today equivalent to £1,505. So, I get why the senior beak was keen to shred my card and cheque book. I’m not going to sell my vinyl collection, I vowed silently. Or my 1960s golden age Marvel comics (reader, I still have them, praise be the Lord as the collection is today worth a small fortune).

But I did clear the debt, slowly but surely, and while it probably took a good while to restore my credit rating to anything less than toxic, that audience with an unamused bank manager taught me a few harsh lessons in fiscal balancing 40 years back.

Funny to think, how four decades ago I couldn’t get hold of cash – back then pretty much the only way so many things could be paid for. You try buying a beer on a debit card in the University of Essex student union in 1979.

And now today, I am thankfully not short of a bob or two but worry that for many of my fellow citizens – particularly the vulnerable and the elderly – that cash is becoming increasingly harder to come by.

As Shakespeare said, ‘The wheel is come full circle.’