A UNIQUE sight greeted local officials gathered in polling booths throughout the UK 88 years ago.

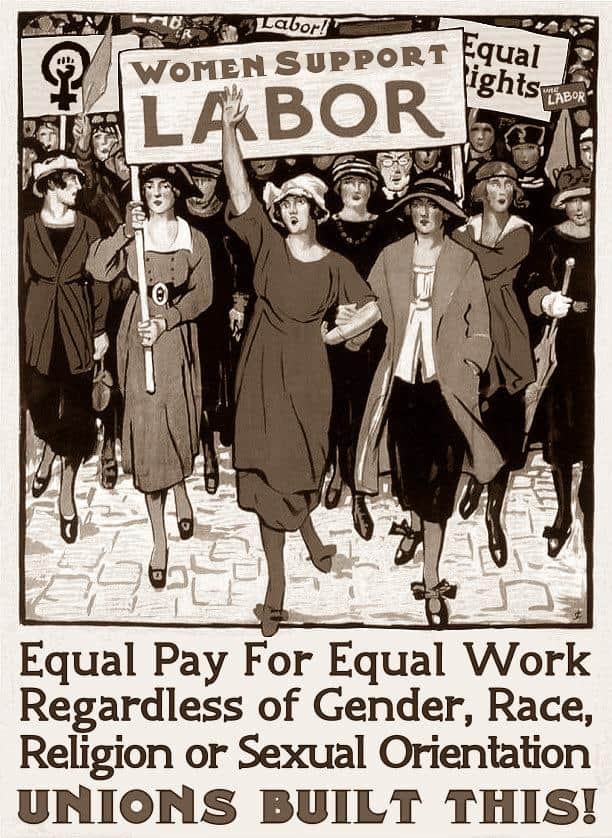

On 30th May 1929, a few short months before Western economies teetered on the brink of wholesale collapse in the wake of the meltdown in US stock markets, many of the eligible voters beating a determined path to add their cross to parliamentary forms were, for the first time in our democratic history, women.

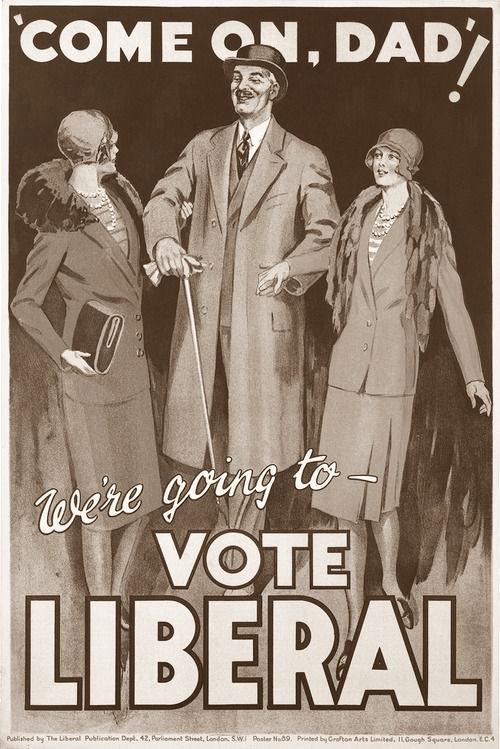

The general election of May 1929 – often referred to as the ‘flapper election’, after the 1920s popular dancers – was the first in which all British women over the age of 21 could vote. The move came in the wake of the Representation of the People (Equal Franchise) Act 1928. It was the final stage in a long parliamentary and gallant struggle for women’s suffrage.

An article published in the Times back in March 1929 estimated that the electoral reforms had added approximately 5 million new women voters. Venerable Times leader writers of the day observed that parliamentary candidates would need more money for printing leaflets, and polling stations might need to be expanded to cope with extra numbers.

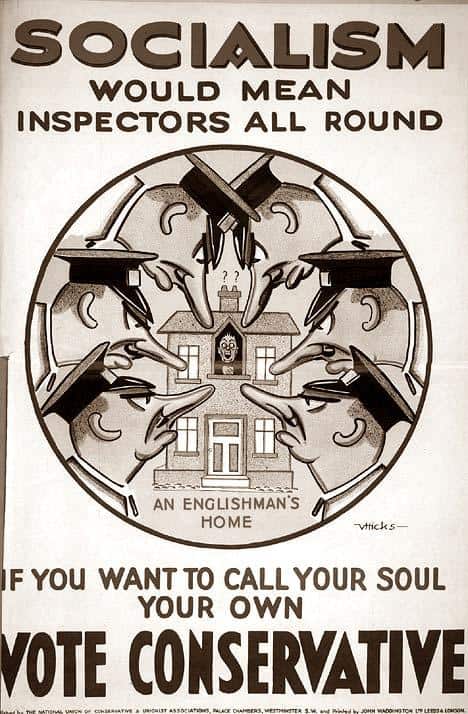

Political parties moved up through the gears, and craftily designed more posters aimed at young women. The Times for example reported how politician Sir Samuel Hoare was organising a party to connect with new voters in his Chelsea constituency.

Many of these prospective voters were, as was the dominant employment for younger women back in those days, housemaids – so the old blusterer’s wife prepared for the event by asking their mistresses to allow them an evening off. Clever, eh?

Unsurprisingly, The Daily Mail in 1929 loathed the idea of women having the vote. Absolutely hated it, dismissing the vote for women as a socialist plot.

Big business was equally alarmed, as if the prospect of millions of women previously denied a view on who should be in power would somehow undermine the very fabric of society.

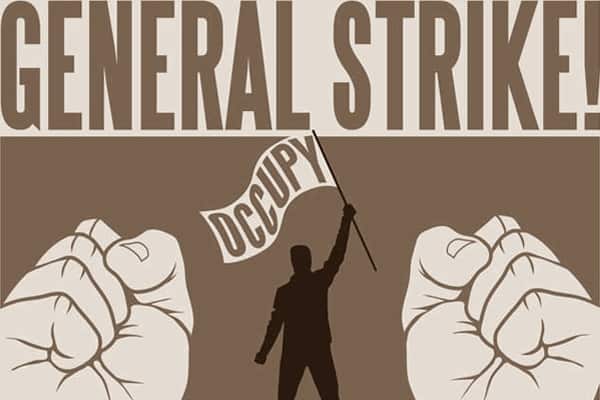

The UK in between the two great wars was in a perpetual state of political and economic nervousness. Unemployment was sky high, there was constant industrial action in the fall out following the Great Strike of 1926, and business and government alike suspected revolutionary comrades were out to depose them at every available opportunity.

My, how things have changed. We have had government led by a woman, with another woman in the key Home Secretary role. Major positions in industry and education are also held by women, not just in the UK of course, but in several other advanced Western societies.

Just as the Tory, Liberal and Labour parties under the old tripartite system all pledged ‘strong and solid’ leadership in their 1929 campaigns, this is also a familiar rhetoric with our government today.

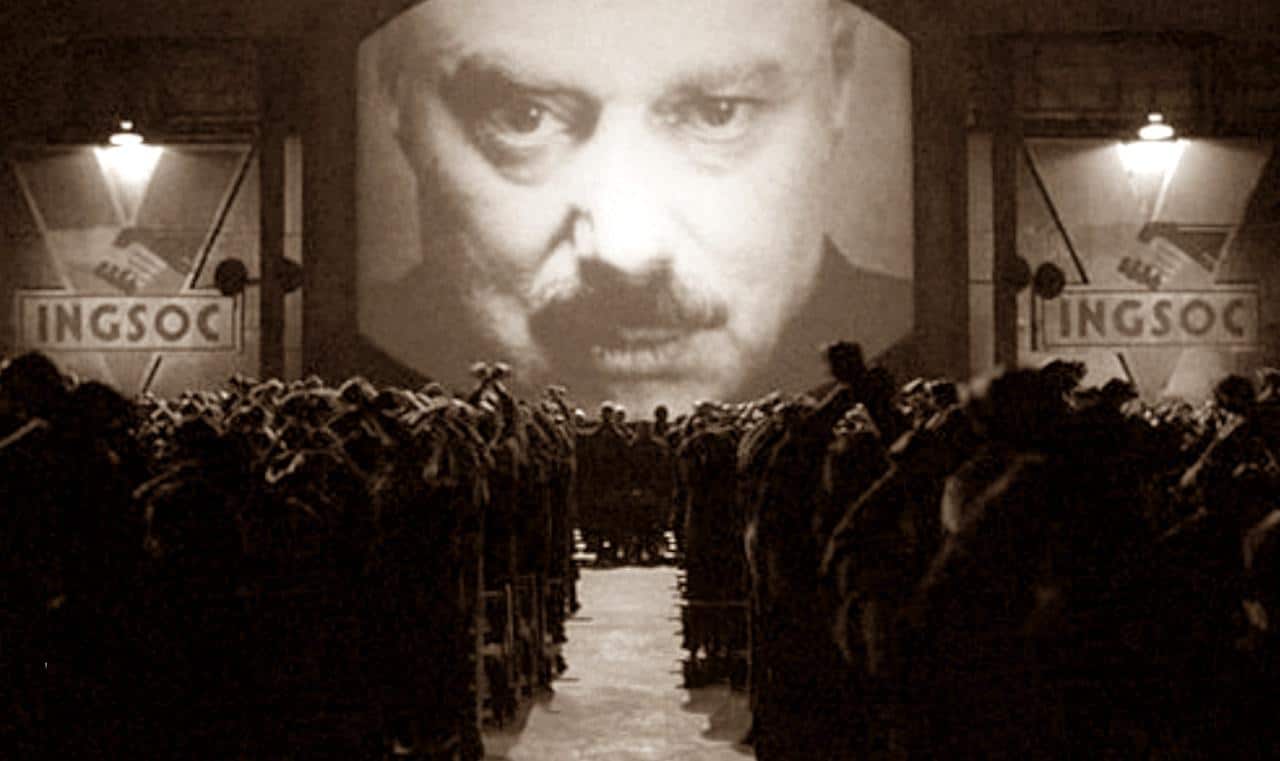

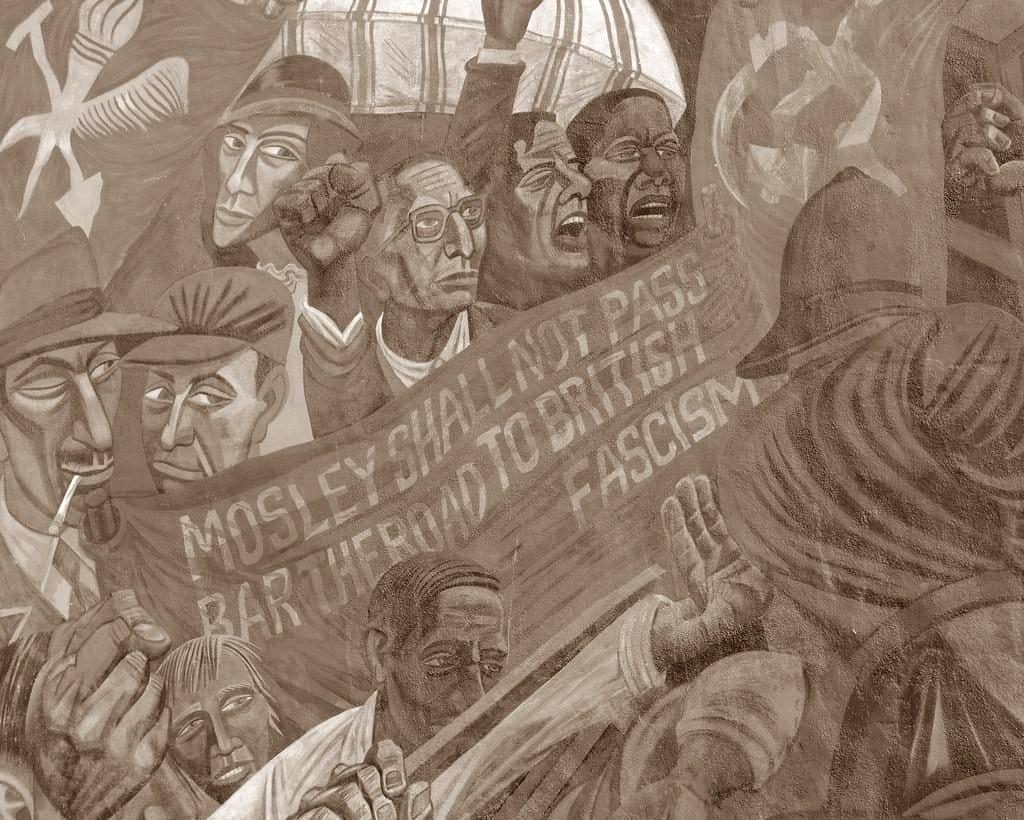

And just as those administrations before us faced the grave threat of Fascism, which threatened to not just destabilise but bring down its enemies completely, government and business also face unparalleled threats in contemporary times.

Terrorism is the grinning imp on the shoulder of all advanced Western societies, and for capitalist-based economies to run smoothly, business needs to be confident that the incumbent administration will be doing its utmost to ensure the work force is protected and that trade channels remain open.

Whichever form of government is with us for the next half-decade, combative rhetoric of defiance has never been more vital or scrutinised.

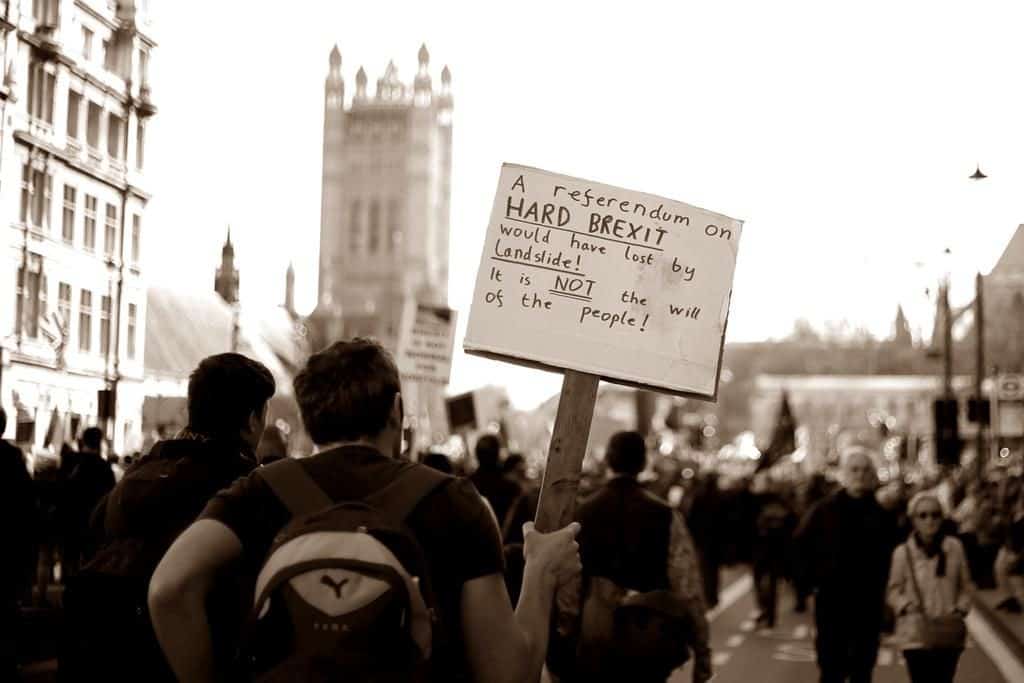

Brexit and its attendant issue will also dominate the political agenda in the coming years – and let us not forget that our economy is still far from out of the woods in the wake of the collapse of the subprime-mortgage market a full ten years back.

The subsequent bail out of the banking sector created a sense of anger towards the financial elite on the part of the many, which turned into a wider frustration with the corporate world.

The crisis triggered a plunge in tax revenues and a sharp rise in budget deficits, prompting governments to pursue austerity programmes that imposed tax increases on many middle-class people and cut the benefits of the less well-off.

Look at Greece. The anger there is palpable. The economies of Spain and Portugal have also been desperately sluggish, and both of these southern European nations have toxic levels of unemployment.

Look also at our own economy, where cuts in public services have created deep apartheid between the private and public sector economies. On the plus side, the UK is currently enjoying unprecedented levels of high employment, and the Conservative administration now finds the economy considerably more stable than when it took over the reins in 2010 in the epicentre of the financial crisis.

Many readers will recall that, on leaving his position as Chief Secretary to the Treasury following the change of government in May 2010, Liam Byrne left a note to his successor David Laws saying “Dear Chief Secretary, I’m afraid there is no money. Kind regards – and good luck! Liam.”

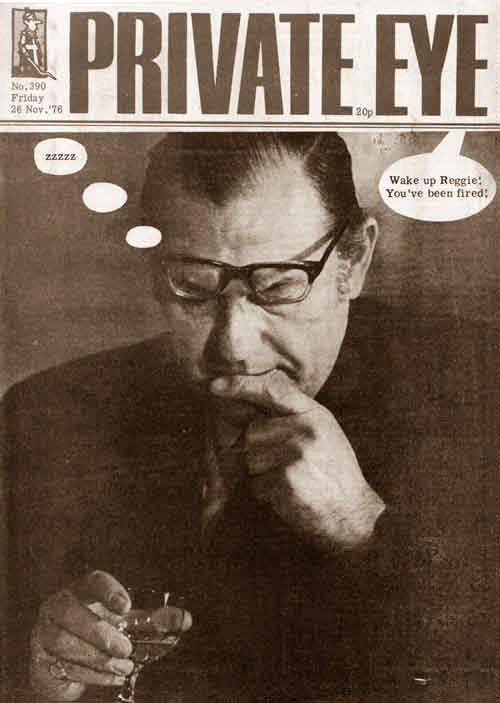

The note echoed Chancellor Reginald Maudling’s infamous “Good luck, old cock … Sorry to leave it in such a mess” note for his Labour successor, following the Conservatives’ shock defeat at the 1964 election.

Many years down the line, there is little room for humour. The business of government, in the face of spreading terror and the unknowns of an unforgiving world outside of the bosom of the EU, is a serious affair.

The world will be watching how the millions of us who comprise this ‘sceptred isle’, – we few, we happy few, we band of brothers (and sisters…) – do not go forward into that long good night without one hell of a fight.

For we have faced dark challenges before, and we have overcome. As we always will.