Revelation 9:7

The appearance of the locusts was like horses prepared for battle; and on their heads appeared to be crowns like gold, and their faces were like the faces of men.

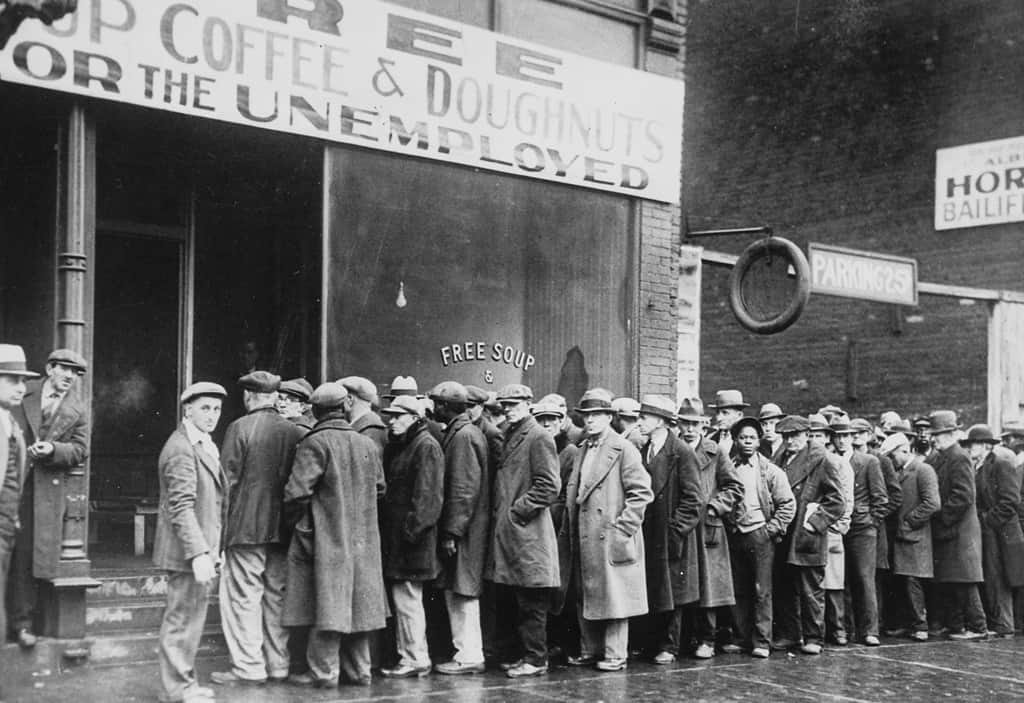

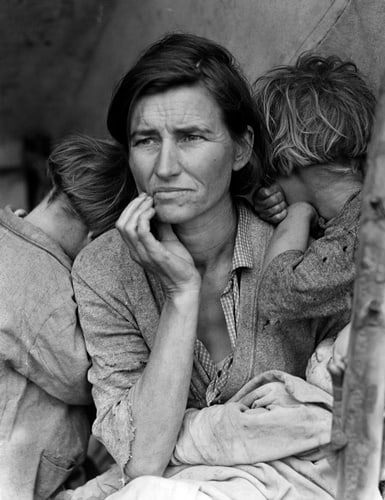

The ten year anniversary of the most devastating financial crisis to hit the UK since the Great Depression of the 1930s is rapidly approaching.

Northern Rock first went cap in hand to the Bank of England on 14 September 2007. On that momentous day the once wildly successful lender sought and received a liquidity support facility from the Bank of England, when it realised it was badly exposed in global credit markets.

‘Badly exposed,’ some may feel, is something of an understatement. The reality was that, following a reckless decade or so of throwing money it did not have after all manner of unsuitable borrowers and dubious investment projects, the Bank had, calamitously, come perilously close a wholesale collapse.

We all remember the queues of worried savers snaking down our high streets, looking to withdraw deposits from a lender once thought to be invincible, such was its stellar rise. Can it really be ten years ago, I suspect you are asking yourself?

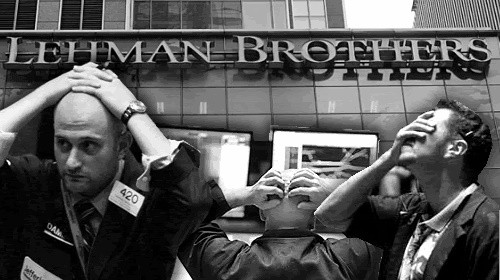

Now, most people will perhaps be thinking, hang on, surely the financial crisis was in 2008, when the big American investment banks – Lehmans et al – began their spectacular collapse? To be clear. Yes, 2008 was when the really big boys started to go under, but the seeds were sown at least a year before, with the build-up of toxic borrowing pre-dating that by some margin.

Back in 1999 I had a front page splash in my then newspaper, warning that lending by Northern Rock was at worrying levels. This was an era of frenzied lending powered by insatiable banks such as Northern Rock, as the second major housing bubble in a decade (readers with longer memories will recall the horrors of the 1989 recession, when millions lost their homes as mortgage interest payments rocketed to 15 per cent) gathered momentum.

Fools, as they say, are soon parted from their money. And Northern Rock proved no different. My news story 18 years ago focused on the fact that the bank was extending not just 100 per cent mortgages – but 130 per cent home loans. Even those with the most rudimentary grasp of basic economics could probably work out that this was a high risk strategy. And so it proved.

With the dawn of 2007, the pigeons were coming home to roost. As soon as the Northern Rock queues started to beam into our livings rooms, the fall out understandably put the frighteners on and consumer spending and borrowing – then at record levels – abruptly began to tail off. This was the Phoney War, the elongated death rattle of upstart lenders such as Northern Rock, fuelled by a belief that the hard landing tomorrow would never come. But of course it did.

When Lehman Brothers collapsed in September 2008, the reverberations almost brought down the world’s financial system. It took huge taxpayer-financed bail-outs to shore up the industry. Even so, the ensuing credit crunch turned what was already a nasty downturn into the worst recession in 80 years. Massive monetary and fiscal stimulus narrowly prevented a return to full scale Depression, but ten years on, GDP is still below its pre-crisis peak in many rich countries, especially in Europe, where the financial crisis has evolved into the Euro crisis. Despite The Trump Effect, the honeymoon period looks to be drawing to a close, and the extraordinary effects of that crash a decade ago are still rippling through the world economy…

Corporate raiders and sleek suited financiers were guilty of taking terrible risks with other people’s money. They claimed to have found a way to effectively banish risk when in reality they had simply lost track of it. The legions of central bankers and other regulators also must answer mea culpa, for it was they who tolerated this financial idiocy. Let’s not forget the macroeconomic backdrop which framed those times of low inflation and stable growth— which ultimately triggered the wild risk-taking. Many European banks were guilty of leeching in American money markets before the crisis, using the funds to buy dodgy securities.

But the crisis of course had its roots in the “subprime” US market, where borrowers with poor credit histories struggled to repay the loans, when interest rates mushroomed, typically a year or so into the debt cycle. These risky mortgages were passed on to the financial geniuses at the big banks, who then turned them into supposedly low-risk securities by putting large numbers of them together in pools.

As the award winning movie The Big Short colourfully enacted, those pooled mortgages were used to back securities known as collateralised debt obligations (CDOs), which were duly sliced into tranches by degree of exposure to default.

Why did investors then buy the safer tranches? Because they were labelled with triple-A credit ratings by the likes of Moody’s and Standard & Poor’s.

Mistake!! Because these credit ratings’ agencies were in the pockets of the banks – they were paid by the banks which had created those very CDOs. And they were not about to bite the hand which fed them.

Today we are in a period of ultra-low base rates and rising inflation, the former an ongoing necessity designed to counter the ongoing fallout from the decade old financial crisis, the latter an inevitable consequence of Sterling’s falling out against the Euro, caught in the slipstream of our Brexit destiny.

Where will this all lead, you may wonder? How is the world likely to look another ten years down the road? By then the so-called millennial generation will be multi-tasking, dealing with the crippling expense of parenting and juggling a mortgage with the uncertainties of employment created by our post-Brexit universe. We are already feeling the chill blast of these momentous world events, and do not appear to have learned the lessons history is clearly telling us. I fear a gathering darkness.