Ghosts. Do I believe in them?

I arrived in Center Barnstead in the fall of ’84. I was optimistic, full of ambition and while it wasn’t exactly a case of go West, young man, I figured that part – heading out to LA – would follow soon enough.

Nestling in the bosom of the White Mountains, an eternity from the nearest Interstate highway and with a population of 4,558 souls, CB –no-one calls it Center Barnstead, apparently – had ignored time. And time itself has obliged and passed by. That’s how the local denizens liked it. Or so it seemed to me.

It was said that even the Sioux Indians, hungry, bullied, harassed and despondent on their long journey north back in the day, gave CB a swerve. Actually detoured to avoid the place.

I’d been in some one horse joints before, but nothing quite prepared me for this.

Nonetheless, the settlement, buried in the deep cleavage of the Live Free or Die state, the one which puts the red into redneck, was where I was destined to spend a couple of months, rehearsing a couple of plays with a US theatre outfit ahead of a national tour.

At least my timing was good. The legendary explosion of colour which emblazoned the region as the dying embers of the summer months turned gently into autumn had turned CB’s environs into a gigantic canvas. It was impressive. Which is just as well, as there was not a lot else to do but gape at the light show nature had laid on for me.

Coming as I did from a perpetually dank and dingy low-rent part of north London, where I had been holed up trying to figure out which turn to take at this still relatively youthful juncture of the journey we all undertake, the dramatic change of scene was good for my head, and, I hoped, good for my wallet. I was after all being paid to rehearse out here.

As I settled in and became a little more familiar with the sparsely populated town, I struck up a few passing acquaintances.

There were a few characters, the usual bar flies with their tall stories, and then there was George.

I liked George, a genial old guy of indeterminate age but I put him at around the late 70s mark, sporting a solitary tooth which protruded like a Cornish crag, glinting occasionally under the generous camouflage of an enormous snow white walrus moustache.

Henry Fonda in The Grapes of Wrath

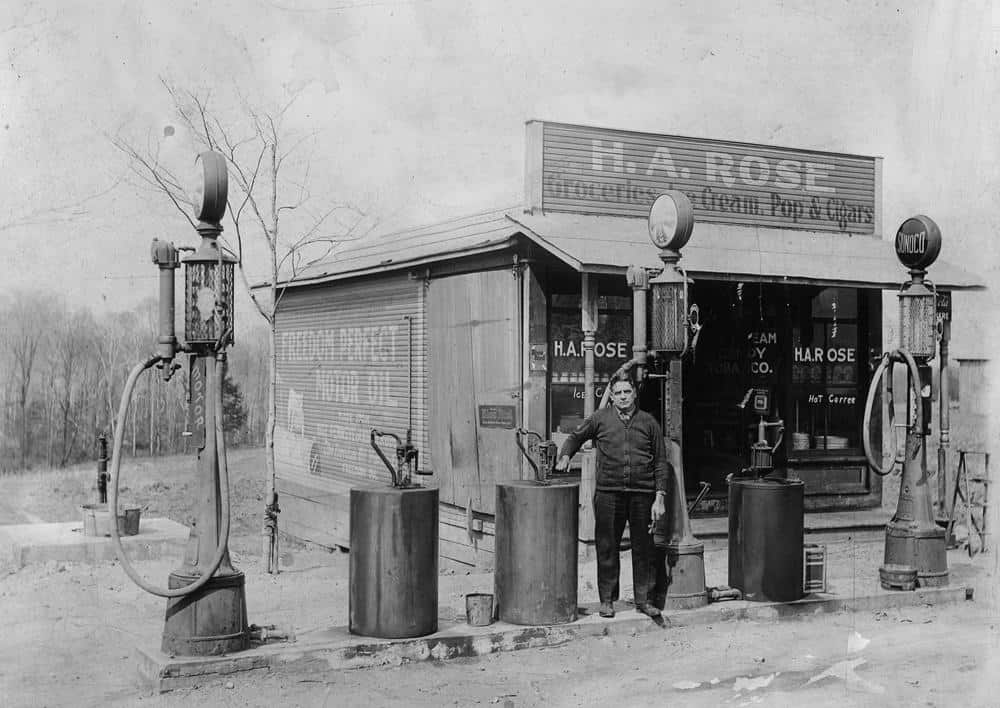

George, invariably decked out in a pair of ancient, perhaps once a paler shade of blue dungarees – of the vintage sported by Henry Fonda in The Grapes of Wrath – ran the town’s only gas station, which doubled as a grocery/diner/hardware store.

Always up for a chat, George would lock onto me with his one good eye – lost the other to a fragmentation grenade just after D Day, he quietly confided early on in our acquaintance – and we would chew the fat. George was puzzled as to why a ‘youngster’ like me was detained by CB.

George, France, near Bayeux, June 1944

Well George, just happens to be where fate has deemed I should go.

But nothing – he pronounced it nutin’ – ever happens, here, son, was a familiar, oft repeated refrain, the way that people approaching the winter of their lives have of forgetting that they had already voiced a sentiment many times over.

Fact is, he cackled, one morning when I popped in for a coffee, needing a pick me up after a fencing rehearsal, last time they had a recorded happenin’ in the area was back in the winter of 1953. Yessiree, 195…3, said George, in a singalong voice, emphasising the ‘three’ in the final syllable.

What happened George, I asked, sipping a harsh black coffee, someone raid the Coca Cola machine out the front, I teased?

Well, said George, straightening up from behind the grime encrusted counter and clearing his throat – a frequent task given that the former combat marine was a three pack a day man (gave ‘em up when I got to 70…the Krauts couldn’t get me but the smokes would sure as Hell’d keep ya warm….)

Somethin’ and nutin’, said George, shuffling out across the shop floor and beckoning me out into the warm late October breeze.

Coupla kids on the run from a job in downtown Boston, he said, gesturing vaguely in the direction of the great city…got busted on some stupid job up in Concorde.

He spat and paused to focus that one rheumy eye on me, gauging as to whether he still held my attention. Didn’t get nutin’, mind, they got plumb rumbled right away, and when they were trying to git the heck our of there they’d fired off handguns – Colts, they both had Colts – at the cops.

Somehow those boys managed to show the Heat a clean pair of heels, boosted a pick up and tore out of there like their asses were on fire.

Critters had been half starved apparently when they pitched up in CB, George gestured expansively at the gently rustling trees framing the store, stole some eggs from the Thomsons down yonder chicken coop.

A long pause, as I feel the coffee buzz and as George, invariably struggling to get enough air into what is left of his lungs….we-llll, they got cornered out in that field back of the Thompsons.

Pointing a bony claw out across the pot holed automobile port in front of the store, George pauses again, like a stand-up comedian, warily biding his time until delivering the punch line of a rambling joke to an indifferent audience…and then all Hell gone done broke loose. There’s prowl cars all over the town like a rash, and cops with tommy guns and shotguns and using loudhailers to get the kids to turn themselves in.

And then these two kids come running out from cover, they’s ain’t no more’n nineteen or twenny years old these two young guns, and there they are the two of them, caught plum in those prowl car headlamps, and looking for all the heck like Butch Cassidy and the darned Sundance Kid, blasting away with those handguns, blam, blam, blam…George trails off, looking down at the dark stain oak boards, liberally puckered with ancient fag butts trodden underfoot, transported back through the miasma of the decades, fragile vocal chords notching up half an octave…and then the heat they opens up, there’s at least a half dozen tommy guns laying down the fire …and those kids, well, he whispers…

They was blown into the next world, son.

They was blown into the next world, son.

George fell silent, looking across the dirt road to the blinding colour of the trees, draped in shadow and framing the store and the White Mountains beyond.

You know what though boy….whatever it was those kids did, whatever wrong side of the tracks they found themselves on, those kids, they was…well, they was brave. Damned if they weren’t. Now long dead and in the ground. They buried ‘em around here somewhere, long forgotten now – unmarked graves, no-one thought too much about the whole sorry business back then. Life was cheap, seemed that way after the war n’all.

Outgunned, outnumbered they was son…ain’t the size of the dog in the fight though, George spat. It’s the size of the fight in the dog, know what I’m sayin’ boy?

I nodded, trying to imagine this deathly silent homestead being turned into a combat zone all those long years ago.

In the silence that followed his graphic recounting of that one-sided shoot out at Center Barnstead in the winter of ‘53, I wonder, was George thinking, about how the years had closed and how much closer to his maker he was now.

I stand before you as an old man who don’t got many years ahead. Most behind. I know I don’t got a lot of time left, and I ain’t gonna pretend I’ve been no stranger to violence. I killed men, said George, flatly. I killed men – German fellas – sure enough in the war. No choice. Had to. He paused, reflected, the store radio crackling, playing an old hillybilly-type dance tune. Killed a lot of men, oh yes. We all did things…saw things, we….He fixed on me, searchingly, that watery, ancient eye locking on, refracted in the gloom.

They say the ghosts of those boys can be seen around here from time to time, whispered George, a shadow passing over his deeply tracked countenance. Terrible thing….terrible, terrible thing…

His voice trailed off and George, shuffling back into the store, glanced over his shoulder.

You believe in ghosts, young fella?

I made to answer, but George was gone, the swing doors gently clacking together in the morning light.

*******

THAT fall of ‘84 it suited me to end up in this deadbeat drive by going nowhere joint.

Not that CB didn’t have its charms. And the odd well known inhabitant, funnily enough. JD Salinger, already long in the tooth by the time I showed up, lived close by. The reclusive legend scuttled around the even tinier hamlet of Cornish, New Hampshire. That was cool, I thought.

I had joined an American touring theatre company. Shivering in a vile flat in north London, the seasons changing and a long harsh winter blowing in just around the corner, going up for endless auditions and being told I was too big, too young, too old too whatever the fuck by some casting director or other and pulling construction shifts for terrible money by day.

So when I did get a call from a guy, Danny Shapiro, who had seen me in a show, asking if I could audition for this adaptation of old Brit yarn The Adventures of Robin Hood why yes, I said. To my astonishment I got the gig, cast as the mad, evil (and very funny) King John, and was on the next flight – more or less – out to Boston.

I hooked up with these American actor dudes for a six week rehearsal period before we hit the road to wow the Stateside audiences. Could be worse, I thought. And besides, I could well end up in LA, maybe I could break into the movies.

Well, I could dream. I passed the days outside of rehearsals with one hour pace runs, followed by hitting the rusting old weights out the back in the barn where we ran through the shows.

There were worse places to be in the world. I liked watching the trees change colour, like in front of my very eyes I kid you not.

How do they do that? There is, I learned, an imperceptible trigger that makes the chlorophyll break down as the trees stop producing the food. So the green disappears, to be replaced by the hues of red, yellow and orange that gives New England that, that look.

Man, those colours. George at the store says you never know just how vibrant the colours will be – depends on other chemical processes, he would muse, pointing a gnarled, heavily mottled and tremulous hand out of filthy, ancient windows and squinting into the midday watery sun. You see the red in those maples? Just how darned brilliant red depends on how much sugar is produced in the leaves and how it gets all tangled and trapped in the chill of an autumn night.

He would look at me, triumphantly, as if he has just stumbled on and finally unlocked the secret of the universe. The more sugar that accumulates, he drawls, the brighter red the leaves turn. That’s how the good Lord made it all happen, George would sigh, perhaps anticipating a pop up appearance from the Man himself.

Y’all ever meet any famous actors, son, George wanted to know. Funnily enough, just before coming out to the States I had auditioned at the Haymarket Theatre for Charlton Heston, by now an ageing bear of a man, who was in town drumming up talent for a newly polished version of The Caine Mutiny, the old Humphrey Bogart vehicle, that he was to direct.

I had no idea I was going to be doing my stuff in front of Chuck Heston. My agent, an imperious septuagenarian and former starlet who was prone to shouting down the phone at me as she was deaf as a post, had advised that a ‘big star’ was coming into town and that she had secured an audition for me. What she had failed to advise was that Ben Cross, fresh from his Chariots of Fire success playing Harold Abrahams, was also going up for the play. I was, once again, about to be blown out of the water.

But I got on well with Chuck (you should address him as Mr Heston, the ASM beaned as she ushered me onto the vast space that was the Haymarket Theatre stage). The first thing I noticed was that he was sporting a particularly brutal hairpiece, slightly crooked, looking like one of those South American flying squirrels which had taken a leap out of a kapok tree and landed fortuitously on the open plains of the great man’s generously proportioned dome.

As a child, I had gasped at Chuck’s skills as the slave chariot driver in Ben Hur, and gazed agog at the big screen of the Burnt Oak Odeon as he flagellated himself in Bible bashing epics such as The Greatest Story Ever Told. And now here he was, flashing me that crinkly smile, one actor to another, the difference of course being that the great ham Chuck was one of the most famous men in the world with a huge body of work under his belt and millions in the bank, and I was me.

Out in the States in CB, I was happy enough. Some days I would join Jonny Shapiro, the younger, tearaway boxer brother of Mike Shapiro, our director for the tour. Jonny was staying awhile, wanting to train out in the White Mountain hills for his next fight. For a boxer, I always thought Jonny Shapiro sure went about his training schedule in a funny way. I would nod to him in the mornings when on my way to the first rehearsals of the day, and Johnny, blowing moodily on a Marlboro Lite and yawning out on the front porch, would nod back.

One gloriously beautiful afternoon in late October, when the colour burst trees were at their most majestic, I finished a rehearsal session early and decided to hit the dirt track for a run. Jonny spotted me pulling on my battered old Nikes, and asked if he could tag along.

Sure, why not I said, glad of the company, but convinced he would be bored with me after the first quarter mile. I fully expected him to take off and leave me flagging in his dust trail. But, to my pleasant surprise, he stayed with me. I was running a lot back then, more than used to knocking off anywhere from seven to ten or so miles, and I could crack a pretty decent pace for a 95 kilo guy.

On that day we stopped off after around three miles and got down to do a bunch of push ups and endless sit ups. Jonny would shadow box while I was doing my sets, and he liked it when I told him I thought he looked like he could do a lot of damage to anyone he met in the ring. A light heavyweight, coming in at a similar 95 kilos to me, the dude looked badass alright.

Ok, let’s hit it again, said Jonny, and then he took off, going from a steady run into something approaching a sprint.

I couldn’t keep up, no matter how hard I pushed myself, arms and legs pumping as fast as I could get the oxygen into me, and Jonny rounded a gentle bend in the road and ran out of my line of sight. As I approached the bend, I felt a sudden chill despite my exertions, as the late October sun on my back faded to be replaced, instantly, by a disconcerting mist – like the pea soupers which suddenly sweep in from the sea just when you do not expect it.

Getting the rhythm of my breathing back, I blinked through the gloom and saw not Jonny but two men, jogging slowly in unison with one another, their backs to me, making an easy pace. They were not wearing running gear. I thought, that’s, like odd, they seemed to be dressed as if of a different era, indeterminate but they both looked to be running in faded dungarees, bluey/grey…a bit like the ones George favoured.

As I ran and kept the runners in my sights, I thought I heard music coming from somewhere behind the densely packed white cedar trees lining either side of the track. It sounded like that slow, waltzy, lazy country music that diner jukeboxes were fond of stocking.

As I ran and kept the runners in my sights, I thought I heard music coming from somewhere behind the densely packed white cedar trees lining either side of the track. It sounded like that slow, waltzy, lazy country music that diner jukeboxes were fond of stocking.

The men seemed to pick up their pace, then slowly, imperceptibly, but definitely, began to fade into the very road in front of me. Hey. Hey!! Hey, I called out, trying for all the world to catch up. I thought I saw one of the runners slowly glance over his shoulder, jet black hair cut razor short at the sides but a fringe lopping down over cobalt blue eyes. I thought I saw him nod, silently. I thought I saw a smile.

Hey, I shouted and waved, hey…HEY!! And then I was looking at a deserted road ahead.

The flame lit cedars bending and whispering to me, the runners now gone and silent as time itself stretching and stretching to the beyond, and as the music died, to be replaced by a mournful rustle of thousands of junipers, larches, hemlocks, pines and cedars, and amid that glorious nature I thought of George 40 years before, and the young men who had fallen beside him on fields of combat and how they were now ghosts themselves.

I thought of the ghosts that had begun their eternal parade through my own life as I looked up and down that road, those who I had known who I would not encounter again in this life.

And I thought of a harsh day in the winter of 1953 when two young men made a bad call in CB and had their numbers punched, and the shadows were lengthening ahead of me and time beats on knowing we have all of us made a mark somewhere in this world and who knows maybe in the next.