Requiem For A Fly Boy

Amersham, Buckinghamshire: November 1973

Hector O’Neill was one of those guys who wanted to fight everyone when he had had a drink.

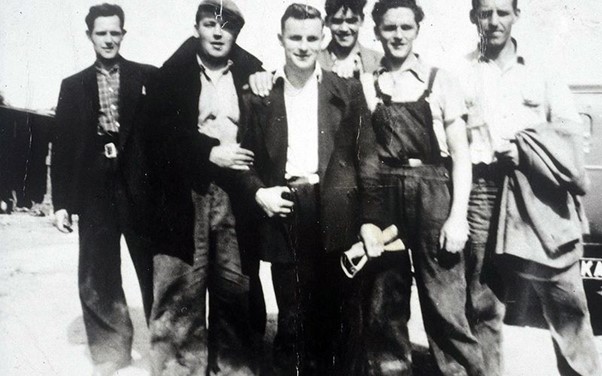

I am telling ye’s, Hector (far left, above) would roar from his perch at the bar of the Iron Horse, if you think you’re man enough, come and say to my face that you can take me. Come on.

COME ON, he would bellow, his face a deep, deep burgundy, partly from the epic volume of pints he had sunk, steadily, lining each one up while still around a third in the previous pint, partly from the harsh, icy winds which whipped unforgivingly through the site where we worked.

Hector would generally stick with the Guinness, but on some lock-ins on a Friday night I had seen him switch over to Mackeson and ciders, typically after he had had a decent skip of Guinness.

The record for the site boys on a Friday, starting at 6pm and going through to the early hours of the following Saturday morning, was 28 pints. They say that this epic number was proudly achieved by Maurice Quinn, (below, far left, white shirt),a 6’4, 23 stone labourer from Donegal.

I for one do not know who was still sober enough to count them. By that stage of the evening – or early morning, depending on how you want to look at it, I would have been drunk as a skunk.

But some blokes could really hold their beer. Maurice, as his unbroken record proudly testifies. And Hector, clearly.

His wing man, Frank Doyle, was another one with hollow legs.

Wiry, with a closely trimmed black beard, and fond of wearing a battered three-piece suit to work, even in those dark and short November days, Frank was slight. Not an ounce of spare fat to be seen on the fella.

But do not be fooled.

The son of a County Mayo fisherman – who, Frank (below, far right), benignly confided one day, drank himself to death by the age of 25, when Frank had just turned seven years old, Frank Doyle and Hector O’ Neill – another Mayo man – would regularly boast they had clocked up the half ton between them.

In everyday parlance, that meant the two had drunk 25 pints apiece. Possibly moving onto the hard stuff before the inevitable collapse onto the filthy, site mud ingrained carpets of The Iron Horse.

Of course, it is physically incredibly challenging to consume such vast quantities of alcohol between the normal pub opening hours when most folk are kicked out at 11pm at the latest.

But lock-ins were one of the myriad attractions of The Iron Horse, to most people’s mind a right shit hole of a drinker, but with a benign landlord and an alcoholic landlady who lapped up the attentions of the men.

I was one of the few English blokes working the site. That said, I played on the fact that half of me – on my maternal side – was Irish.

My mother, descended from a long line of small holding farmers in County Mayo, was lucky to have made it to motherhood at all, given the massively high rate of infant mortality in southern Ireland in the early years of the 20th century.

Maybe it was the Irish in me which saw me gravitate towards these rough and ready men, who would prefer to punch you first and ask questions later if they thought you were cheeking them.

But I knew my place in the pecking order. Blokes like Hector and Frank were skilled. That is, they were both expert paving slab layers, and slab layers in the early 1970s were at a premium.

It also meant that they were, by the standards of the times, extremely high earners. Both would be on piece work, so the more slabs they laid, the more money they would earn.

While I was an unlikely candidate for such brutally hard labour, I had earned my stripes by offering to be their dedicated labourer. That meant I spent those long days going back and forth from the dumper trucks with their loads of wet concrete on my back, staggered under the weight of paving slabs, pausing only to jump back onto the dumper truck to fetch more wet concrete for the boys to lay down their expertly cut slabs.

C’mon, c’mon, Hector would constantly urge, no time to hang about here. There are beers to be drunk and girls to be visited, he would cackle.

Both were handsome men in that rugged, out-doorsy way. Both had that sharp, Oirish sense of humour.

And on those freezing cold, brutal winter days, when the starting handle of the dumper stuck to your hands because of the deep frost and you could not feel your toes despite the newspaper lining your boots, we would all pile into the battered old wooden hut where Audrey, a sweet tempered, endlessly patient local woman, was preparing the men’s breakfasts.

If the men had an appetite for consuming vast quantities of beer, their collective appetites for a site breakfast, usually consumed at 10 am on a weekday after a couple of hours of hard labour, was nothing short of extraordinary.

As 10 am approached, most of the men on the site would contrive to be working in the vicinity of the canteen. The reality of course, is that we were all hovering around hoping to get through that shabby door as quickly as humanly possible, shouting our orders to Audrey and her team of helpers in that steaming, smoke filled kitchen.

Hector and Frank, both fleet of foot and invariably in the throes of a wretched, Def Con 10 hangover, would be among the front runners.

Double egg! Double Sausage!! Double bacon!!!Double tomato…and DOUBLE beans…no, make that TRIPLE SAUSAGE!!!! and four rounds of toast if you will Audrey, I’ll be thanking you now, they would shout, making a bee line for the table nearest the counter and warmth of that hard pushed kitchen team.

When the food came, which to be fair was commendably quickly given the limitations of the space and the frankly challenging size of the orders, the men, after looking solemnly for a micro second or so at the steaming pile of sustenance spilling over the out-sized, chipped and off white plates, would dive in, wolfing it down as if their lives depended on it.

If this was a race, I would think, then I know I am nowhere in the running. If I was a betting man, and I could be, from time to time, if I sensed the odds were reasonable, then I would have put my money on the gargantuan man mountain Maurice Quinn. I had Maurice down as the eating champ of that exclusive gang.

From a huge Mayo family – Maurice was one of seven brothers – the guy could not only drink everyone under the table, but had the appetite of a grizzly bear awakening after a long winter’s hibernation.

After demolishing the teetering plates of breakfast grub, the men would gulp down heavily sugared, steaming mugs of tea, while rolling their fags and, invariably, cracking jokes.

So, boys, who’s going for the crack tonight, bellowed Frank, piercing blue eyes dancing up and down the rag tag band of brothers on his rickety table. Ye’s will have ,money in your pockets, he added, eyes twinkling….and IT’S GOING TO BE A HELL OF A NIGHT LADS, he shouted.

The whoops that followed Frank’s exhortations pleased the slab layer, beaming as he took took a long draw on his fag.

I couldn’t picture Frank without a fag on the go. Come to think of it, the only time I didn’t see Frank with a fag dangling Robert Mitchum style from the corner of his mouth was when he was shovelling down a plate of grub or downing a pint of Guinness. Both of which he was a master of effici ency.

ency.

I’m in, said Hector, raising one arm in the affirmative while masticating on the final scraps of his epic breakfast.

Should be a great crack alright, he added – where are ye’s thinking….don’t tell me the Iron fucking Horse again?

Ahh be -Jesus fucking Christ almighty not that shit hole again, echoed Maurice at the far end of the table. You’d think that was the only pub in the whole of the fucking universe alright..

But the opposition was genial and said with an air of tacit resignation. We all knew that there was only one pub for miles which would tolerate the excesses of the gang.

And, to be fair to The Iron Horse, yes, it was something of a dump, but assuming we were allowed into the saloon bar – it depended on the mood of the landlord – then there was a pretty good chance that there would be some women there.

And one young woman in particular, a, 18 year old absolute stunner called Sandra Robinson, who I’m pretty sure quite liked the cut of my jib.

I’d clocked her demurely looking across the bar at me some evenings, and once, when I popped David Bowie’s Starman on the broadly shite jukebox, Sandra positively beamed behind her heavy strawberry blonde fringe.

I wasn’t a bad looking young man. Tall – a little over 6 foot, and I liked to dress well. A decent pair of Levi 501s paired with a cut off T and some nifty Adidas Chile’s. Now we are talking, my son.

And, although I had only just turned 18 years old, my youthful body had already filled out with long months of brutally tough physical labour.

Maybe she would be there later tonight, I thought, abstractedly rehearsing a potential chat up line. These scenarios rarely play out as we would like, but I thought, if I could stay sober long enough to string a sentence together, then I would at the least be in with a fighting chance.

Maybe, I thought, I could extend an invitation to the local Indian joint. Push the boat out on a curry. Flash the cash, she might like that, young Sandra.

Yes, summon up the courage, dig deep, casually give Sandra the nod…fancy a curry later…?

What do you have to lose? Fear of rejection, yes, but it could be the start of something great. Me and Sandra.

Often on a Friday night, around chucking out time, some of the boys would cross the road to the Taj, which many would argue is the world’s worse Indian restaurant.

Granted, you took your life in your own hands eating there, and most of the men had at one time or another been poisoned by one of the Taj’s legendary mutton vindaloos (make it as hot as you can fella and be sharp about it!!).

Eating there was a high risk endeavour, be in no doubt of that. But when you have consumed a skip full of Guinness with generous Jack Daniels’s chasers, it was invariably a risk worth taking. Not sure if Sandra would see it that way, but hey, nothing ventured, nothing gained, as they say.

When I arrived at the pub, perky after a hot bath and smelling divinely – I thought – of Brut following a quick scrape around – both public and saloon bars were already filling up.

I could see the boys through the glazed, filth ingrained panes of the back bar, and could hear the strains of Danny Boy wafting out into the freezing November night.

As most of the regulars in the public bar were of Irish descent, the landlord had shrewdly put in a separate juke box, filled with standards from the mother country. The Chieftans, The Dubliners, plus a host of crooners – Val Doonican was in there, one of my mother’s favourites.

I read somewhere that Danny Boy was the most played tune in Ireland’s history – possibly even the States, too – well, most of that Boston lot and a big chunk of New York City identified as Irish, so no real surprises there.

Perhaps the landlord had this in mind when stocking his ancient jukebox. I spotted three versions – one by Jim Reeves, which is the one most of the men seemed to favour, one by that big bearded dufus Roger Whittaker, and another slow tempo rendition by Glenn Miller and his orchestra.

Jesus Christ. Don’t think we will be getting any Led Zeppelin on this ‘box any time soon.

Sometimes, if they had enough beer inside them, the men might attempt a dance to a lively Dubliners tune.

If they were lucky, occasionally one of the few women brave enough to withstand their lurching, slurred advances, might perhaps out of pity, have a dance with them. But it was rare.

I popped into the back bar first of all, spotting both Frank and Hector at the bar, quietly sipping their pints.

Also there was Maurice Quinn, blocking out half the light with his massive bulk, and, nice surprise, I saw in the far corner, keeping his own counsel as ever, Yankee Colin.

Wrapped in the grubby flying jacket he wore 24/7, Yankee Colin, or YC as we sometimes called him, was stroking his generous handlebar ‘tache, like some devious villain in a cheap B movie.

Bizarrely, the displaced American was a former reserve US air force pilot who claimed to have seen action towards the close of the Korean War. How he had ended up on a construction site in early 1970s England was anyone’s guess.

Rumour had it he had married into a wealthy country family in the Sixties and come to live in London: but even by the standards of the rough and ready Mayo boys, YC was one hell of a drinker and it wasn’t always easy to get a straight answer.

The former combat pilot was nursing what looked to be a quadruple scotch on the rocks.

Like many men with his deep level of alcohol addiction, he topped up through the day, and when I finally beat a pathway through to his table he looked to be well on the way to being good and properly shit-faced.

Colin, who had not got round to changing out of his muddy site gear, worked the huge and dangerous looking concrete mixer, and I would often chat with him when sat on my dumper waiting for a concrete load to pour into the truck’s skip, invariably with Frank and Hector’s roaring at me to be quick as these fucking slabs are not going to lay themselves.

That Colin had fallen on hard times was an understatement. He was the only one of the men to actually live on the site, emerging from a tiny, freezing caravan parked near the canteen, at the start of the shift.

No-one knew how the battered old caravan happened to be on the site – probably abandoned by the traveler community who had lived on the land before it was bought by the developers.

And the site foreman, a benign English guy called Arthur, was happy for Colin get his head down there, turning a blind eye for the most part to the big American’s occasional benders. This was the 1970s. Things were different back then.

How are you fella, I shouted, trying to be heard above the roars of my fellow workers and the deafeningly loud music.

He-eeyyyyyyy, say, how you doin’ young fella, asked the ageing fly boy.

Yes, all good YC, I shouted, leaning in to make myself heard above the Friday night exuberance.

Not drinking with the boys, I asked rhetorically.

Colin was a loner, and while he was generally pretty well liked, most of the Irish fellas kept to their own clan, regarding Colin as they might a rare, exotic creature which had somehow pitched up in their midst.

For my part, I always thought Colin to be cool. In his more lucid moments he would quote some of the great writers. How would Hemingway look at it, you have to ask yourself, he would say…

I bought Colin a beer with a whisky chaser, although to be truthful he did not need any more booze.

I asked how he came to be in the caravan, but he shook his head, slowly and deliberately. Married a rich girl, he said, finally. I strained closer to hear.

Extraordinarily rich but let us just say…. he paused, looking for the right words. Let’s just say it didn’t work out fella, added the airman finally, with a final sigh, like an old sofa being jumped on by an obese occupant….but as F Scott Fitzgerald put it, he said, lowering his voice to barely above a whisper….’it is sadder to find the past again and find it inadequate to the present than it is to have it elude you…. and remain forever a harmonious conception of memory’.

And with that I was unconsciously dismissed by Colin, his eyes beginning to glaze over already – my cue to switch to the saloon bar – who knows, maybe Sandra was in with some of her pals, I thought, checking my look in the vast mirror which adorned the rear of the bar area.

It was a mission to elbow my way into what passed for the posh bar, but there in the far corner, nodding earnestly, deep in conversation with one of her chums, was Sandra.

She was trading heart to hearts with a heavily made up girl who sometimes did shifts behind the bar.

Hovering awkwardly (but I hoped still retaining a vestige of cool), I thought if I remained just within the gorgeous Sandra’s peripheral vision, then I could ambush her, that is if she ever came up for air – whatever they were discussing it looked to be of solemn importance.

I’ll cut my losses, I thought, just as David Essex came on the juke box, which on balance, if you are going to split, then being spared a wanky David Essex tune was not a bad cue on which to make tracks.

Another epic round of elbowing my way through to the heavy old door – more like a portcullis than a door – which linked through to the public bar, to reveal the boys in full tilt. Frank and Hector, both wild eyed and animated, still perched at the bar, locked in a desperate arm wrestle.

I never underestimated Frank’s strength, despite his slight profile, the guy had serious underlying power. Hector, however, exhibited the brutal force of a man who had been brought up lifting hay bales from an early age, and it looked like a contest which was only going to go one way.

I had on occasions seen the men brawl among themselves, usually when off their faces and so perhaps not entirely on their game.

I had seen many men, no longer in the first flush of youth, guys who should maybe have known better, pounding away at one another in a drunken frenzy, despite their advancing years.

But hey, as Schopenhauer once had it, … remember, only once you’re over the hill you begin to pick up speed.

The great gladiators of ye ancient times rarely became old. Dudes just did not live that long back then, and most of those fellas became croppers in the arena, one way or another.

Dudes like Theogenes, who it was said went into solo combat hundreds of times, fearless. What did he have to fear, after all was said and done? What were the alternatives if he did not fight?

For this was an age without reason, an age before the enlightenment of Aristotle and Socrates….a world without Plato and the maybe an age as yet entirely devoid of wisdom, where savagery was the order of the day. Dog eat dog, and if Theogenes was worried about cashing in his chips legend has it that he never showed it.

The men gathered in the public bar of The Iron Horse that Friday night in late November, the closing days of 1973, while the world was going to pot all around them, striking miners, striking power workers, everyone seeming to be striking apart from construction workers.

Maybe they were not striking because they had no coherent union to organise them. Blokes working on building sites in those days were natural mavericks, the majority – who I encountered at least – Irish, often itinerant, and picking up work where they found it.

And also men like Colin, displaced, no direction, hustling a living where they could. Sitting quietly in an anonymous corner of a bar, hoping their lives would pass without too much more pain and disappointment.

Danny Boy has come on the jukebox once again. Patsy, a wild-eyed fella from Connemara, is joining Frank and Hector in a less than harmonious impromptu rendition, leaping up onto the bar, waving his pint like a madman.

O Danny boy, the pipes, the pipes are calling

From glen to glen and down the mountainside

The summer’s gone and all the roses dying

It’s you, it’s you must go and I must bide

But come ye back when summer’s in the meadow

Or when the valley’s hushed and white with snow

‘Tis I’ll be here in sunshine or in shadow

O Danny boy, O Danny boy, I love you so

And when you come and all the flowers are dying

If I am dead, as dead I well may be

You’ll come and find the place where I am lying

And kneel and say an Ave there for me

And I shall hear, though soft your tread above me

And all my grave shall warmer, sweeter be

For you will bend and tell me that you love me

And I shall sleep in peace until you come to me

And as they sang along, I saw the man mountain Maurice, clutching the side of the bar to steady himself, with tears streaming down his broad face. His lips moving silently within that vast, spade like face.

Missing the home country, perhaps, missing a girl left behind long ago, missing the legion of brothers with whom he would fight for the scraps on the dinner table. Missing his place in a world he no longer understood, missing, maybe, the notion that he might one day become a father, and hoist his children upon those vast shoulders.

And then I saw Maurice standing over Colin, bending down, shouting above the roar of many drunken voices raised in a form of tuneless harmony to the strains of Danny Boy.

And, as I started to push my way through the men and dense fog of Sweet Afton and Golden Virginia cigarette smoke, I could see Maurice was now cradling Colin in his trunk like arms, and I knew then that Colin had gone, the life drained from him.

Maurice – who we knew to look up to Colin, maybe as the father figure he had never had growing up in the combative arena of the farm – now shaking the American’s lifeless shoulders, crying out his name, Colin, Colin…..wake up Colin…wake up fella.

Would ye wake up for Christ’s sake, he whispered, with a child-like pleading.

But the gods had called time on Colin. It was Last Orders for this fly boy, the final mission.

Those cobalt blue eyes which had once flashed so brightly, and who knows, had once fleetingly held a Korean MIG pilot in his gun sight while streaking across a harsh Asian sky at 700 mph, were now closed forever.

As the strains of Danny Boy fell away the men stood in stricken silence, someone said to call an ambulance and Maurice, down on one knee, cradled Colin, brushing the American’s straggly grey hair back from his unseeing eyes.

He was a fine man alright, said Maurice. You were alright, fly boy. You were alright.

Ends