demon

[ˈdiːmən]

NOUN

- an evil spirit or devil, especially one thought to possess a person or act as a tormentor in hell.

“he was possessed by an evil demon” ·

[more]synonyms:

devil · fiend · evil spirit · fallen angel · cacodemon · incubus · succubus · hellhound · afreet · rakshasa

‘Ghost hunting’ …. a popular term for the investigation of potentially paranormal, site-based anomalies, such as apparitions, poltergeist activity… unexplained noises. Many practitioners prefer the term ‘paranormal investigator’.

Extracts from The Diary of Doctor George Stephens Lacey: Brighton

Monday, 11 January, Year of Our Lord 1919

On this bitterly cold January day, it is my grave misfortune to have once again received Lieutenant James Carmichael MC, into my surgery.

Lieutenant Carmichael, a man said to have exhibited outstanding bravery in the dreadful conflict, has become a familiar face in recent weeks.

I must confess, my mood, which is typically upbeat, drops markedly when the young officer is announced.

Even on a clear, crisp winter’s day such as this, where a prevailing gentle wind and cobalt blue sky conspire to raise one’s spirits despite the desperate cold, the thought of having to calm the young lieutenant is unwelcome – and contrary to my professional training.

One should be always empathetic to the needs of one’s patients, I recall my former senior colleague Dr Arthur, late of this parish, gently chiding me.

And the old goat was right, of course. As he invariably was.

But then, I sighed, Dr Arthur did not have to deal with the constant babblings of a man clearly teetering on the very edge of emotional breakdown.

Each visit has become progressively more emotionally fraught than the preceeding consultation.

To recap: It had been my (initial) professional opinion that the lieutenant has been suffering from a type of psychological trauma incurred while in the service of the King.

Currently on leave from the army on grounds of ill-health, although the reasons for his debilitating condition have yet to be established by military authorities, I am resigned to seeing a good bit more of the fellow.

In his most recent visit my housekeeper, Mrs Garland, had to assist in my endeavours to calm him when he started with his near hysterical babbling. Before he had even removed his hat.

Now, Mrs Garland, who in a previous life was a front-line nursing sister in the Boer War, is a most capable woman. Totally unfazed, as befits one who is no stranger to suffering and battlefield carnage, she is also exceptionally practical.

‘Perhaps doctor,’ smiled my indomitable housekeeper, ‘a small dram of whisky may have benefits far beyond my mere mortal medical powers. Should I pour one for the young gentleman?’

Glancing up from my notes, I nodded my silent assent. Let’s attempt to at least calm the chap before all hell breaks loose.

The facts…as they have been presented to me, appear, on the surface at least, rather ordinary. Some might say bland.

Lieutenant Carmichael – who lost his wife, Mrs Marianne Elizabeth Carmichael – to the dreadful Spanish ‘flu in November last year – has conveyed, in his more lucid moments, his feelings of intense guilt.

Normally a (in my experience), personable, dignified, and sensible young gentleman, the poor man believes he infected his hitherto healthy wife with the killer virus.

That would have been shortly after returning home from the front following the end of the conflict in France.

The virus claimed Mrs Carmichael within a matter of days. Gone in a flash, just as it has decimated entire town and villages the world over.

Extraordinary, how an ostensibly healthy young woman could be struck down with such horrific finality.

The couple were, perhaps fortuitously, childless. And, even in his ramblings, there is no denying the deep affection the soldier held for his late wife.

But whereas when he initially came to me complaining of not being able to sleep and of having highly disturbed dreams, the situation has subsequently deteriorated.

Dramatically so.

Now he appears to have become quite, well, quite mad. He insists that his wife has returned from beyond the grave. Back to haunt him, no less.

Naturally, as a rational sceptic, I attribute notions as one for the popular picture books. How on earth do people get taken in by this kind of nonsense?

Even the most illustrious of minds seem to fall for these idiocies, these fantasies of an active after life. Mr Charles Dickens, for example, was a fully paid-up member of that most ridiculous of institutions, The Ghost Club.

I mean, really, a man of such fabulous imagination and creativity. But surely that is where the speculation should end.

A fellow member, I understand, was Mr Siegfried Sassoon, now emerging as one of our greatest war poets.

It is perhaps not coincidence that the most revered Mr Sassoon was himself admitted to a military psychiatric ward – doubtless his mind had been significantly unhinged by the dreadful horrors of the trenches.

But now, faced with the distressing rantings of a man who one presumes looked death in the face time and again while in service, I confess to being at a loss as to how to progress.

‘She is out there doctor,’ he virtually screamed at me in today’s fractious hand wringing session.

‘Wherever I go I feel her – and this morning I saw her….I know it was ….it was her….my, my dear Marianne..

‘She comes to me…day-time…night-time, there is no rhyme or reason. Rather the rats in the trenches than this living hell – yet I do not wish to move on from her memory, you understand, doctor?

‘But my waking life has become intolerable. Yesterday, for example, she appeared to me when walking through the cemetery. I had paid a visit to lay flowers on her grave.

‘As I knelt to offer a prayer I became aware of…of Marianne.

‘She, she was hovering above the ground doctor, he hissed…..hovering….’ the unfortunate soul virtually shrieked at me.

The lieutenant slowly sank into the surgery chair, cupping his head in his hands, shaking, and trembling as if….

‘….as if he had seen a ghost …’

Wednesday, 13 January, Year of Our Lord 1919

Following Monday’s distressing encounter, I decided to solicit the view of a long-time friend and professional associate, Professor Michael Henry.

My esteemed associate and I go back several years. Whereas I have settled for general practice, Professor Henry has made quite a name for himself.

His growing reputation is largely by virtue of his papers on the theme of emotional illness- (many have been published in the esteemed Royal Society of Medical Practitioners Journal) – the most recent being ‘On the Mythology of the Spectral Apparition, June 1917.

The professor also attends meetings of The Members of the Society for Psychical Research (SPR), which to my limited knowledge is an organisation grounded in reason – but with a door left open to any compelling evidence of paranormal activity.

One of my friend’s colleagues in the august club is a Mr TF Thiselton-Dyer, whose early theorizing on alleged hauntings included doubts about the ability of a ghost to cross water – so, they can hover but they cannot cross water, I thought.

Again, the rationalist in me took over. Emotional illness – also known by some as a ‘mental state’ – is currently occupying some of the most revered minds in medical science.

Although here I must confess, I remain very dubious as to whether the latter is indeed a medical condition.

For we are governed by the parameters of science and the illustrious frontiers of medical research.

Of trial and error down the centuries, from the carnage of the battlefield to the madhouses of our great industrial cities.

And if science cannot prove the lieutenant’s condition to be medically valid, then how can I, a humble local doctor in service to the greater good of my community, assist?

Professor Henry and I agreed to meet at his club, The Brighton Gentleman’s Forum tucked away in the recesses of Brighton’s Ship Street, which lies but a stone’s throw from the promenade.

There are, one is constantly aware, many dangers lurking in the shadowy arches of the town, and no doubt many ruffians enjoy some rich pickings to be had from visitors on their occasional days out from our great capital city.

But if one keeps one’s wits sharpened, there is little or no physical danger to one’s self – and there is a constant police officer presence outside our gentleman’s club. An additional deterrent to the ever present menace of violence on the streets of Brighton.

“Right,” said the professor, tilting a generous glass of port in my general direction and taking an appreciative sip, “tell me about your patient. I am all yours.”

Both rational beings, I was naturally apprehensive about outlining my patient’s insistence that he was being haunted by his recently deceased wife.

We are sceptical creatures by nature, the professor and I, and I knew him to be – as indeed I am myself – a disciple of Mr Darwin.

The suggestion that spectral beings- humans in non-human, demonic form exist, is anathema to us both.

And yet, given the clear distress of my youthful patient, and my obvious concern, the professor agreed to join me in my next session with the allegedly haunted man.

“Given that the lieutenant has first-hand experience of the horrors of Flanders, and the stresses that must have effected, I would be amazed if he – or indeed any of his professional soldier contemporaries – returned from the Front without some degree of emotional stress,” he said.

“But let us be clear my good doctor, if your patient’s fears are to be taken seriously, then we need to see evidence. For it is only with evidence that we can derive clarity. And without clarity, why, then we are nothing. And life will remain a puzzle, an enigma.”

We enjoyed a most convivial time – and a decent amount of port I should add – under the gaze of the magisterial portraits of former members. When I left the club, a little unsteady on my feet I should add, I felt something of a weight off my chest, having shared my troubled thoughts with a man of such exceptional intellect.

Saturday, 16 January, Year of Our Lord 1919

With no surgery duties to attend, and the promise of skies finally clear of the pummelling rain which has plagued the south coast in recent days, I decided to embark upon a late morning constitutional.

Sea air, as has been scientifically proven, is vital to our general well-being. Combined with a stretch of the legs, it is dashed near unbeatable.

As I wandered, I thought of my time in Brighton since arriving here at the outbreak of war, five long years ago.

I thought of the past. Is it sadder to find the past again and find it inadequate to the present, I wondered, than it is to have it elude one and remain forever a harmonious conception of memory? Who can say?

I made my way from my modest dwelling on Stanley Road, a decent, professional neighbourhood, and navigated the increasing incidence of motorised traffic at Preston Circus, picking up my pace while navigating the lurking hazards of London Road.

Ignoring the beggars and con artists which plague these parts, I hastened my stride, coming to the green space known as The Level on the approach to St Peter’s church.

Despite the relatively early hour, there was no shortage of women peddling their wares. Many were already considerably inebriated.

One particularly persistent young woman I found hard to shake off, despite her exhortations that she would ‘do me’ for two pennies. I was not tempted, but I did linger momentarily at a showman’s drably cladded stall, which promised to give ‘The Fright of Your Life’.

What was this alleged fright, I enquired of the swarthy looking ruffian who stood outside the attraction, bellowing to all and sundry to come and get a really good scarin’.

‘If it please you sir, you will need to step inside the tent and – silent as you like, mind – sit yourself down opposite the young woman. You’ll encounter her once inside the tent,’ he chuckled with a foul gargle.

It’s the best half’penny you are like as not to spend today, sir, I guarantee it by all that is not Holy.’

His grin was more of a leer, and as he leaned his heavily pocked countenance in towards mine, I became aware of a most dreadful odour, a rotting, foul stench.

So bad it was, the ghastly, open sewer-like smell reminded me of my days as a trainee physician in London, dissecting corpses, a fearsome, dread eau de mort which will stay with me for the rest of my days.

As I was in no particular hurry, in a broadly upbeat frame of mind, and to a degree tempted by the titillating promise of a cheap scare, I pressed a halfpenny onto the showman’s grubby paw and entered the makeshift tent.

Once inside, the thickness of the canvas did a fine job of blotting out the watery January daylight. Hanging on the sides of the tent were primitive illustrations, of the kind an amateur pavement artist might knock up.

The images were of ferocious looking demons, all horned hooves, and blazing red eyes and forked tongues.

Despite my scorn for such trifles, I had to admit to a growing sense of clamminess. There was a stifling airlessness under the canvas, and I made to loosen my collar.

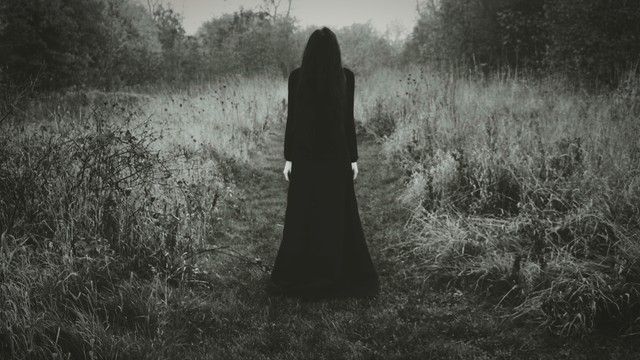

And then I saw her.

In the gloom, illuminated by a sole flickering black candle, there sat, perfectly still, a woman, perhaps in her mid-twenties. She was dressed from head to toe in a sombre, subtly shimmering black.

Just above her left breast I made out a gold-tinted brooch, fashioned in the shape of a heart. It looked to have a teardrop, seemingly weeping from the heart’s centre.

Gazing mutely directly ahead of her, she did not acknowledge my tentative presence, and despite my awkward attempt at a casual greeting, the women stared silently ahead. Utterly immobile.

As instructed, I perched in front of her on the sole chair provided. There was barely an arm’s length between us, and up close, I could see her features picked out in the flickering candlelight.

She was pale, deathly pale, but her visage was illuminated with a rash of bright red lip stick steaked across her mouth.

A decorative black veil obscured the upper half of her face, but it was possible to ascertain symmetrical features, sharp, high cheekbones. A beautiful woman.

I sat, and as I waited for something, anything, to happen – I had no idea what to expect other than the showman’s wink and a nod that I would be frightened out of my wits – a hidden gramophone began to play some deathly, low choral music.

With the strains of the background music, the gloom of the tent and the faint smell of incense – such as that which might be used at a Catholic mass – an intense fatigue fell upon me.

And as I regarded the young woman, she inclined her head towards me, in a barely discernible feline movement.

As she slowly leant in towards me, I could see her lips begin to part, revealing brilliant white teeth ring-fenced by the intense rouge.

‘Yes’, I could hear myself begin to speak…and then the young woman suddenly opened her mouth wide, like a yawning chasm before me. And unleashed a shrieking, blood-curdling scream.

So loud it was that I fell back from my chair, terrified, and, while floundering on my back, was aware of the woman bending over me.

It seemed she was hovering a few inches off the ground, arms by her side, her entire being unsupported… hovering ……and again came the deathly, spectral scream, as if hellishly conjured from the legions of the long dead.

I scrambled to get to my feet, and lunged out instinctively, but the woman was gone. Vanished. I was alone in the tent, shaking, bathed in a cold sweat and in dread for my life.

Flailing my way out of the tent, I emerged, panting, in a state of deep terror. Ashen faced, I stumbled towards the showman.

‘How did you like it sir….give you a fright did she,’ he beamed, flashing a mouthful of rotten black molars.

‘What is that…that thing in there,’ I said, my wretched terror gradually making way for anger.

‘She frightened the living daylights out of me,’ I snapped.

‘Where is she, where did she go?’ I demanded of the now sniggering vulgarian.

He regarded me, a sinister grin playing around his unshaven mouth.

‘She comes and goes good sir, comes and goes, she does.

‘Some say that she has special powers…maybe even inhabits the body of a young woman who passed before her time.

‘Mind you,’ he added, lowering his coarse tone to little more than a whisper, ‘there’s times I have thought, little darling, you’re so pale you could be an actual spirit.’

Hurrying away from the Level, with many a fearful backwards glance, I dodged the weekenders and riff raff to be found around the West Pier and carried on walking out towards Hove.

It was my intention to head north up one of the great boulevards modelled on the open style so prevalent in Paris. Probably I will make for The Drive, I thought.

Despite the brightness now of the afternoon, try as I might I found it hard to lift my troubled mood.

The encounter with the ghostly fairground woman had more than alarmed me. I had been shaken to my very core. And here I am, a rational, reasoned man of medicine.

Heading north in the direction of Hove Park, with the lengthening shadows of the day closing in, and a faint but persistent rumble in my stomach, I decided that what I most needed was a hot meal and a glass of two of ale.

I stopped at the bustling Albion public house, and, once I had navigated the baying, crowd of patrons and choking fug of tobacco smoke, was pleasantly served by the most enormous, beaming landlady.

Perusing a grubby copy of the Evening News and filling my pipe with a good pinch of old shag, I was mildly detained by a report that Germany was headed for complete bankruptcy, such was its runaway inflation.

They brought it upon themselves, I thought, appreciatively imbibing by turns on a long draught of ale and a deep pull on my pipe.

Sometimes, I thought, only a beer and a smoke will do the trick. I had also ordered a mutton pie, with potatoes and a good helping of cabbage topped off with a thick gravy. That would address the rumbling tummy.

The public house was sparsely furnished. I sat in the saloon area, while across from me I could see – and of course hear – the rowdy public bar area. They were doing a storming trade.

A story on page 3 of my newspaper revealed that many disenfranchised Germans had flocked to join a new political movement, The German Workers, which had just been set up in Munich.

Heavens, I thought, have they not had enough of politics? Whilst proving the most resilient and courageous of enemies, I for one did not think for a moment that the defeated German race would simply roll over and accept their fate. But let us hope that we will not be enjoined in warfare again any time soon. Enough lives have been needlessly wasted.

And then I gloomily reflected on my patient, the haunted – allegedly – lieutenant. I daresay I will be seeing him again soon enough, I reckoned.

I had not been called up, despite my repeated attempts. A faint heart murmur had excused me from active duty, and my medical training had grounded me here in Brighton.

We always need good local physicians, barked the affable recruitment sergeant when I first responded to Lord Kitchener’s exhortations to join up.

That had not stopped a group of young women approaching me with foul language and presenting me with a white feather back in the heat of the conflict.

A coward, they had called me – one had even followed me down North Street, cursing and shouting that I should get myself onto the next paddle steamer for France and DO MY BIT, she had bellowed.

That was getting on for 5 years ago now. How time flies, I reflected, when my internal reverie was interrupted by the arrival of the biggest plate of food I believe I have ever laid eyes on.

‘Another tankard, sir,’ winked the landlady, looking at me in what I interpreted as a most flirtatious manner.

‘I most certainly would, madam – in fact, would you be so kind as to bring an accompanying glass of cognac to wash it down with please. I would be most grateful.’

As I wolfishly devoured my meal and drained the outsized tankard of its pleasingly hoppy contents – a fine local Kentish brew – I found my spirits begin to lift. The fire blazing away in The Albion’s vast open hearth also helped immensely, and all thoughts of spectral beings and hideous, core-penetrating screams drifted away.

Then, as I was draining the last of my beer and contemplating my cognac chaser, I became aware of a sudden drop in temperature – despite the roaring fire.

Looking across the room, through the dense smoke of innumerable pipes and rolled cigarettes, I saw, to my stunned surprise, standing at the public bar, the woman. Dressed head to toe in black, the veil falling over her brow.

Good Lord, I thought, what on earth….for a woman to be in a public house was rare. To be in the public bar of a public house was even less common an occurrence.

As I gawped across the room, her face turned slowly towards me.

Despite the veil, I could see lurked the darkest of coal black eyes, their gaze now boring into me.

The din from the bar seemed to have stilled, and I could not make out any of her fellow patrons, for she seemed to fill the room itself.

And then I heard – and I swear by all that is holy – the woman speaking directly to me.

Even though she was at least 20 paces away, with a bar dividing us. it was a whisper in my ear, a harsh, urgent whisper…..’find me….’ she, or should I say it, seemed to be saying. ‘find me….find me…….’

I looked up from my half-devoured plate, and there in front of me she now hovered, shrouded by dense smoke and ambient gloom, but there she was perhaps three or four inches from the ground.

Again I saw the heart brooch adorning the fabric above her left breast.

‘What do you want with me. WHAT DO YOU WANT’, I shouted, leaping out of my seat, only to find myself being restrained by a pair of burly young men, each one firmly gripping my arms.

‘Steady sir, steady – hold him Stan, hold him,’ said the man to my left. The landlady, no longer smiling, was now at my table, ‘sir, sir, I think it’s probably time to leave now sir,’ she said gently, clearly thinking I had imbibed more alcohol than was good for me.

‘Did you see her’, I said, looking urgently from one to the other. ‘Did you see her,’ I hissed again.

‘Who sir, see who – there’s ain’t no women folk in here sir,’ she soothed…’most wouldn’t be foolish enough to come into the Albion, rain or shine. It’s just who you see around you sir.’

Monday, 18 January, Year of Our Lord 1919

Within the walls of my surgery, I felt, if not totally secure from any further inexplicable encounters, then at least I was surrounded by the tools of my trade, my learned journals, and the ambience of science and reason.

Of course, the events of the weekend had shaken my equilibrium to the core. The shoe was firmly on the other foot.

It was I who had been reduced to a gibbering wreck, but did I really experience a visitation from the other side, as it were?

Perhaps I will never know, but one thing I knew for sure. I was prepared to receive the lieutenant this morning and be solemnly respectful of his revelations.

In short, I resolved to no longer be inclined to a default position of doubt.

At 11 am on the dot the redoubtable Mrs Garland ushered in the lieutenant.

He looked pale, but the mania which had previously consumed him appeared to have lifted. He seemed, to my mind, to be, well, relaxed.

‘And how are we today,’ I asked, glancing at the gentleman’s medical notes, which were spread neatly on my desk.

I had heavily underlined the words ‘traumatic stress??’ and ‘post combat disturbed state???’

‘Thank you doctor,’ he said, smiling; I think for the first time in our many meetings.

‘Oddly enough I am feeling miraculously much better. The, um, appearances appear to have stopped.

‘But more specifically, I feel that my dear departed wife has, has moved on. I have a notion, inexplicable given recent events, that she may be…may be at rest, finally.

‘At peace,’ he added, his voice at once mellifluous and reasoned, in utter contract to the shaking wreck who sat before me barely 7 days previously.

I nodded, ‘good…good, that’s excellent. I have to say,’ I said. ‘You appear to be vastly more relaxed. It is wonderful to see,’ I added, wondering if it could be remotely conceivable that the events of the weekend had somehow led to a transference of the stresses my patient had been under.

The lieutenant advised that he had decided to resign his commission and take his leave of England.

‘I am going to explore, doctor, explore the wide world, and see where it takes me. I have a notion to see the great pyramids of Egypt. Not a bad place to start, eh,’ he said, extending his hand to mine.

‘I am so grateful to you doctor,’ he added, as he was about to exit the surgery.

Turning to face me for the last time, he produced from his waistcoat pocket a small, neatly bound package, delicately woven with a fine red bow.

‘I’d like you to have this, as a memento of our brief time together…of our, discussions,’ he added, cryptically, placing the package on my desk.

‘Farewell doctor,’ he said, pausing at the door.

‘If we do not meet again in this world, then who knows, we may meet once again in the next.’

I thanked him profusely, insisting there was no need for any such gift.

But my words fell on deaf ears, the lieutenant swept out of the surgery and – if I am truly honest – I hoped my life.

Once I had written up my notes and closed the young soldier’s case file, I glanced at the package lying on my desk.

Delicately removing the fine bow, I opened the wafer- thin paper, there to reveal a solitary, gold-plated brooch. In the shape of a heart, with a single tear weeping from its centre.

Ends c David Andrews February 2021